Energy twilight and the new politics

©

The headlights pushed hard into the void—the lights seemed too weak to do the job. I squinted my eyes, yes, there it was. The incoming tide, as inky dark as the black abyss, was flooding silently—almost evilly—over the gravel bar. We’d stayed too late to race the tide. For the first time we were stranded on the island.

“That’s Ministers Island,” I thought. I put the car in reverse, being careful not to spin the wheels in the soft gravel, and backed up onto the island. I looked at Sharon. She laughed. It was a good thing we’d set up the gardener’s cottage for the island farmers. There was an extra bed, so we’d at least get some sleep.

We got off the island the next morning at sunrise, and got started on a new week. I had some building supplies to pick up at Kent’s, and while there caught the headline of the day’s Telegraph-Journal: the provincial government had announced talks with Newfoundland and Nova Scotia to create a power tie-line between Churchill Falls in Labrador with New England—through New Brunswick. “What a great idea,” I thought, and one that occurred to me before, when the Shawn Graham government was wrangling with the public over the Hydro Québec deal. I’d even mentioned the idea to our Fisheries minister, Rick Doucet, when they were in the middle of the debate—and before they scrapped the Québec deal. Who knows how these seeds get planted, but it’s great when something good takes root.

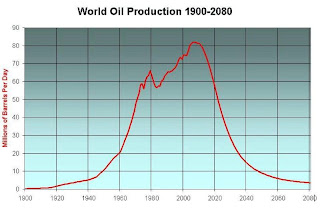

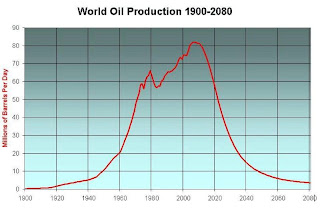

Energy, especially alternative energy, will be the defining issue of this century. With the global consumption of oil at 80+ million barrels A DAY and growing, not to mention the consumption of coal for electrical generation, we’ll be needing vast amounts of the alternative variety before too long. Experts such as Matt Simmons and Matt Savinar think that we will fall off the top of “peak oil” curve as quickly as we went up.

According to one graph, we’ll be out of the bulk of our oil by the year 2050—just 40 years from now. If you’re a sucker for punishment or fear, you might want to check it out at http://www.oildecline.com/or http://www.lifeaftertheoilcrash.net/. Here’s a snippet from this last one:

According to one graph, we’ll be out of the bulk of our oil by the year 2050—just 40 years from now. If you’re a sucker for punishment or fear, you might want to check it out at http://www.oildecline.com/or http://www.lifeaftertheoilcrash.net/. Here’s a snippet from this last one:

“The issue is not one of “running out” so much as it is not having enough to keep our economy running. In this regard, the ramifications of Peak Oil for our civilization are similar to the ramifications of dehydration for the human body. The human body is 70 percent water… A loss of as little as 10-15 pounds of water may be enough to kill him. In a similar sense, an oil-based economy such as ours doesn't need to deplete its entire reserve of oil before it begins to collapse. A shortfall between demand and supply as little as 10 to 15 percent is enough to wholly shatter an oil-dependent economy and reduce its citizenry to poverty.”

In other words, we’re all going to feel the pain of oil depletion long before 40 years out. The next 10 years will be crucial. And that’s where it comes down to political foresight.

We need our politicians to begin thinking longer than their 4-year terms. The decline of fossil fuel will affect every aspect of our lives, from cheap food to the work that we do to the whole notion of a global consumer society. Without inexpensive fuel to power our transportation system, the global economy as we know it will grind to a halt. And then what?

There are two bets. The first is we will find enough alternative energy over the next 15 years to migrate our global economy from a fossil-fuel driven system to another system. The second bet is getting ready for the possibility that we won’t make the switch in time. That would mean relocalizing, retooling and reskilling our regional economies.

Well, the energy tide is going out, and from our behaviour, our heads are firmly planted in the sand. And our politicians are mostly concerned with getting elected. I met with one candidate last week, a good guy. He asked me what I thought about LNG projects across the bay in Maine. I told him, as I’ve written here before, that LNG is on the table simply because there have been so few economic opportunities in northern Maine, and people are desperate for decent jobs. Across the bay they see us as affluent, hypocritical NIMBYs who don’t want LNG in our backyards, but don’t mind having LNG in Saint John.

“So you’re a Maine LNG supporter?” he asked. I said, no, running tankers through our local waters is a bad idea, and there are better places and better ways to offload LNG, offshore, for example. That said, in the years to come, I think we’re going to want as much LNG as we can get—at least if we want to keep this lifestyle going.

And as politically popular as maintaining our current lifestyle may be, that may not be possible. There simply won’t be enough cheap energy to go around. We’re rapidly approaching the dark abyss.

The headlights pushed hard into the void—the lights seemed too weak to do the job. I squinted my eyes, yes, there it was. The incoming tide, as inky dark as the black abyss, was flooding silently—almost evilly—over the gravel bar. We’d stayed too late to race the tide. For the first time we were stranded on the island.

“That’s Ministers Island,” I thought. I put the car in reverse, being careful not to spin the wheels in the soft gravel, and backed up onto the island. I looked at Sharon. She laughed. It was a good thing we’d set up the gardener’s cottage for the island farmers. There was an extra bed, so we’d at least get some sleep.

We got off the island the next morning at sunrise, and got started on a new week. I had some building supplies to pick up at Kent’s, and while there caught the headline of the day’s Telegraph-Journal: the provincial government had announced talks with Newfoundland and Nova Scotia to create a power tie-line between Churchill Falls in Labrador with New England—through New Brunswick. “What a great idea,” I thought, and one that occurred to me before, when the Shawn Graham government was wrangling with the public over the Hydro Québec deal. I’d even mentioned the idea to our Fisheries minister, Rick Doucet, when they were in the middle of the debate—and before they scrapped the Québec deal. Who knows how these seeds get planted, but it’s great when something good takes root.

Energy, especially alternative energy, will be the defining issue of this century. With the global consumption of oil at 80+ million barrels A DAY and growing, not to mention the consumption of coal for electrical generation, we’ll be needing vast amounts of the alternative variety before too long. Experts such as Matt Simmons and Matt Savinar think that we will fall off the top of “peak oil” curve as quickly as we went up.

According to one graph, we’ll be out of the bulk of our oil by the year 2050—just 40 years from now. If you’re a sucker for punishment or fear, you might want to check it out at http://www.oildecline.com/or http://www.lifeaftertheoilcrash.net/. Here’s a snippet from this last one:

According to one graph, we’ll be out of the bulk of our oil by the year 2050—just 40 years from now. If you’re a sucker for punishment or fear, you might want to check it out at http://www.oildecline.com/or http://www.lifeaftertheoilcrash.net/. Here’s a snippet from this last one: “The issue is not one of “running out” so much as it is not having enough to keep our economy running. In this regard, the ramifications of Peak Oil for our civilization are similar to the ramifications of dehydration for the human body. The human body is 70 percent water… A loss of as little as 10-15 pounds of water may be enough to kill him. In a similar sense, an oil-based economy such as ours doesn't need to deplete its entire reserve of oil before it begins to collapse. A shortfall between demand and supply as little as 10 to 15 percent is enough to wholly shatter an oil-dependent economy and reduce its citizenry to poverty.”

In other words, we’re all going to feel the pain of oil depletion long before 40 years out. The next 10 years will be crucial. And that’s where it comes down to political foresight.

We need our politicians to begin thinking longer than their 4-year terms. The decline of fossil fuel will affect every aspect of our lives, from cheap food to the work that we do to the whole notion of a global consumer society. Without inexpensive fuel to power our transportation system, the global economy as we know it will grind to a halt. And then what?

There are two bets. The first is we will find enough alternative energy over the next 15 years to migrate our global economy from a fossil-fuel driven system to another system. The second bet is getting ready for the possibility that we won’t make the switch in time. That would mean relocalizing, retooling and reskilling our regional economies.

Well, the energy tide is going out, and from our behaviour, our heads are firmly planted in the sand. And our politicians are mostly concerned with getting elected. I met with one candidate last week, a good guy. He asked me what I thought about LNG projects across the bay in Maine. I told him, as I’ve written here before, that LNG is on the table simply because there have been so few economic opportunities in northern Maine, and people are desperate for decent jobs. Across the bay they see us as affluent, hypocritical NIMBYs who don’t want LNG in our backyards, but don’t mind having LNG in Saint John.

“So you’re a Maine LNG supporter?” he asked. I said, no, running tankers through our local waters is a bad idea, and there are better places and better ways to offload LNG, offshore, for example. That said, in the years to come, I think we’re going to want as much LNG as we can get—at least if we want to keep this lifestyle going.

And as politically popular as maintaining our current lifestyle may be, that may not be possible. There simply won’t be enough cheap energy to go around. We’re rapidly approaching the dark abyss.

Comments

Post a Comment